Origin Stories – Pulling on the Thread of Commoning

Categories Capitalism & Free Markets, Commons (Nonprofit) Sector, Commons Management, Cooperatives, Nonprofit Management, Private Sector, Public Sector, Stewardship, Systems Thinking, UncategorizedThe proposal of an Undersector, a sector that exists beyond and outside of the three that are recognized today, begs a question of origins. What are the histories and historiography of the Undersector? If the state, private, and charitable sectors describe most, if not all of the geography of possession and control today, how is it that we may even sense there’s something else, another realm? There are some clues in the origins of Western law and political economy.

Today’s sectors have largely been defined by Western (European) law, government, and political economy, which has in turn colonized and defined commerce across the globe. This should be our first clue that we have only part of the picture. The concepts of political economy that came to dominate the early modern period in Europe from the 17th Century forward have a much more diverse and ancient set of peers, some of which would appear to trace lines of influence to our contemporary notions of possession and control.

One of these is commoning, whose ideas appear in practically every indigenous culture around the globe. We might say that commoning is the archetype of how humans have intuitively and practically approached maintaining resources that have a value to the collective. Each family in the village has a cow, but there is only one meadow. How do we manage its use together and avoid overgrazing? Commoning, in the most basic sense, is the act of maintaining or stewarding a specific shared resource through the work of a defined but open group of individuals who, in turn, benefit from that resource. As such, commoning shares many values and concepts with cooperative and other forms of collective action: governance by the people benefiting from the resource, clarity around the rules and processes of stewardship and sharing the resource, and commitments to ongoing community building and learning.

Even though the original commons were (are) largely land and natural resources, anything can become a commons: money, ideas, technology, buildings, raw materials, equipment, human labor, even legal forms. Commoning ideas show up today, though furtively, in things like the Creative Commons license, open-source software like Linux and Drupal, and urban lots that are taken over from absent landlords by communities for use as gardens and open space (squatting and adverse possession). It is important to point out that commoning is first and foremost a verb, a collective act of stewardship, not a collection of things (a noun). Land is not intrinsically a commons resource. A piece of land that is being stewarded by a group of people free of private ownership interest is a commons. There is no commons without commoning.

Commoning always includes structures for governance and accountability, but it is not predicated on notions of title-holding ownership that define the assets of the state, private, and charitable sectors. No single person or specific group of people owns the commons. It is this attribute that brings commoning close in concept to the present-day status of charitable or nonprofit sector assets, which are held in public trust.

Since federal tax-exempt status applies to corporations, and in the U.S. corporations are a state matter, the resources of any given nonprofit are the “property” of the people of the state where that nonprofit is legally formed. Assets may be legally titled to the nonprofit, but they are for the benefit of the public and thus belong to the people. (This is true even if the organization’s mission operates beyond the borders of its state, nationally or internationally.) As public trust assets, nonprofit resources ultimately fall under the jurisdiction of the state’s Attorney General or Orphan’s Court, which represent the interests of the people of that state. The status of commons and nonprofit assets, while not identical, thus share the similarity of collective attribution. This inspired me to venture down the rabbit hole of commoning. This exploration was initially intended to be an archaeology of the charitable sector, attempting to diagnose its seemingly intractable foibles and perennial failures. The bottom of that particular rabbit hole remains elusive, but the journey so far has yielded some potentially new diagnostic views of the nonprofit sector.

The origins of commoning as a recognized political economy in the Global North lie with the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (482 – 565 A.D.), whose rule encompassed the period of renovatio imperii, or the restoration of the Roman Empire. By the time of Justinian’s coronation in 527, the empire was in a bit of disarray. It had lost control of some of its Western territories and was stitched together by a hodgepodge of legal and financial systems–the precarious remnants of Rome’s insatiable appetite for conquest. One of Justinian’s great legacies was his organization of the empire’s vast and fragmented legal system, memorialized in the Corpus juris civilis. He began this project by first creating a simple taxonomy of possession–why not start organizing laws by describing different kinds of owners? His Institutiones (one of the books of the Corpus), describes four kinds of ownership, laying the foundation for our modern sectors:

- Res publicae – or things owned by the state

- Res privatae – or things owned by private individuals

- Res communes – or things owned by people collectively

- Res nullius – or things owned by no one

Res nullius is by far my favorite, including at the time of Justinian such things as the sky, air, and oceans. Today, sadly, res nullius has all but vanished as an idea, wiped from the face of the earth by the rapacious appetite of res privatae and its powers of possession or “enclosure”. It would seem that everything has been subjected to ownership by one of the other three sectors, such that private and state interests have nothing left but to train their avarice on the moon and the stars.

Res communes describes, of course, the domain of commoning, and it’s notable that there was recognition of the practical need (and apparent existence) at that time for a category of possession that was neither the state nor private, but still capable of addressing the interests and needs of a group or community (not just an individual person or family). If you work in the nonprofit sector, this particular group of beneficiaries should sound familiar.

While there are rich commoning histories and literatures in many cultures, beyond Justinian, we will focus on England, as its Common Law is the foundation of contemporary U.S. nonprofit law. The era of King John of England laid the foundation for modern jurisprudence with his famous Magna Carta and its lesser-known companion, the Charter of the Forest, issued in 1217. You don’t learn about the latter in grade school, but it’s one of the first significant documents about commoning. It concerned the management of England’s forests for common use and is noted for its remarkably open, yet managed approach to defining commons stewardship.

Leaping forward again from King John, we land at the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, who in 1601 issued the first legally defined, secular concept of social benefit in the English speaking world: The Charitable Uses Act or Act of 1601. Elizabeth, also known as the Virgin Queen or Gloriana, ruled England during one of its richest social, cultural, and economic periods of development. Refusing to marry and bear an heir, she is said (apocryphally) to have been “married to her people”. Perhaps it wasn’t a coincidence that the first codified idea of social benefit, birthed by the state and free from any religious mandate, was conceived by the likes of Elizabeth.

The Charitable Uses Act does not occupy a place in most commoning histories, but perhaps it should. Justinian’s res communes survived through the Modern Era, but not as a dominant political economy. One of the reasons for this marginalization may have been that it was culturally sublimated (supplanted) through the invention of the modern charitable sector, an approximate conceptual relative.

The current American tax-exempt sector, with its many peers around the world, was modeled on the Act of 1601, essentially replicating its ideas through the evolution of our charitable tax legislation from the Tariff Act of 1894, through the nonprofit sector’s formative advent with the Revenue Acts of 1913 and 1917. The latter two established tax-exempt organizations and the individual tax deduction for charitable gifts. In Elizabeth’s Act, ultimate oversight over charitable funds was granted to England’s local nobility. In adapting that authority to 20th-century America, the states’ Attorneys General replace the nobility as ultimate fiduciary.

To bring this speculative historical fly-over full circle, we land with the architect of contemporary commoning thought, the American political economist Elinor Ostrom (1933-2012). My own journey in commoning began about a decade ago when I read her wonky but electrifying work, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge University Press, 1990)–the Bible of modern commoning. Ostrom got her start thinking about the commons by working on water rights (one of the classic commons resources) in California in the 1960s. Her interests in commoning quickly led her to mount a refutation of the notorious thesis, the Tragedy of the Commons, first introduced in 1833 by British economist William Foster Lloyd.

The Tragedy of the Commons thesis essentially says that any commons, such as our grazing pasture from earlier, will be grazed into oblivion by the individual interests of the community if people are left to their own devices. Commons = Tragedy at the Hands of Human Self Interest. Right around the time Ostrom’s work was taking off, Lloyd’s theory was wrested from obscurity, significantly dusted, and supercharged by economist Garrett Harden in a landmark 1968 article in Science magazine. Harden’s affirmation of Lloyd’s thesis found popular appeal among the growing Neoliberal economic thought of the late 1960s and its supporters. As Roosevelt’s New Deal entered its twilight hours, policymakers were looking for any argument they could leverage against pro-social economic policy from the state; the free market, guided by the optimizing virtues of private interest, would set all things right.

Ostrom launched her offensive on Hardin’s thesis, waging a two-front battle, one mathematical, the other anthropological. Her main assertion is that the Tragedy of the Commons is a straw man. It assumes an ungoverned, unmanaged, ruleless approach to the commons, which would indeed lead to decimation. BUT, that isn’t how commons are actually stewarded.

To add punch to her argument, she reached for then-new-ish field of game theory (largely the work of John von Neumann and John Nash) and adapted its mathematics to commoning, creating the sub-field of Common Pool Resource Economics (CPRE). (Ostom’s prose is wonderfully precise, but if you’re like me, you can skip the pages of math proofs.) This level of mathematical rigor had never been applied to the dynamics of commoning and granted the field an aura of “mature” science. Second, and more interesting, she set out on an ambitious anthropological project to study the actual day-to-day management of a range of ancient commons around the world: highland meadows in Switzerland, irrigation system in Valencia, rice paddies in southeast Asia. One of her criteria for inclusion: the commons had to be continuously stewarded for more than 500 years. She wanted cases that had stood the test of time, war, famine, natural disaster, and the wax and wane of empire.

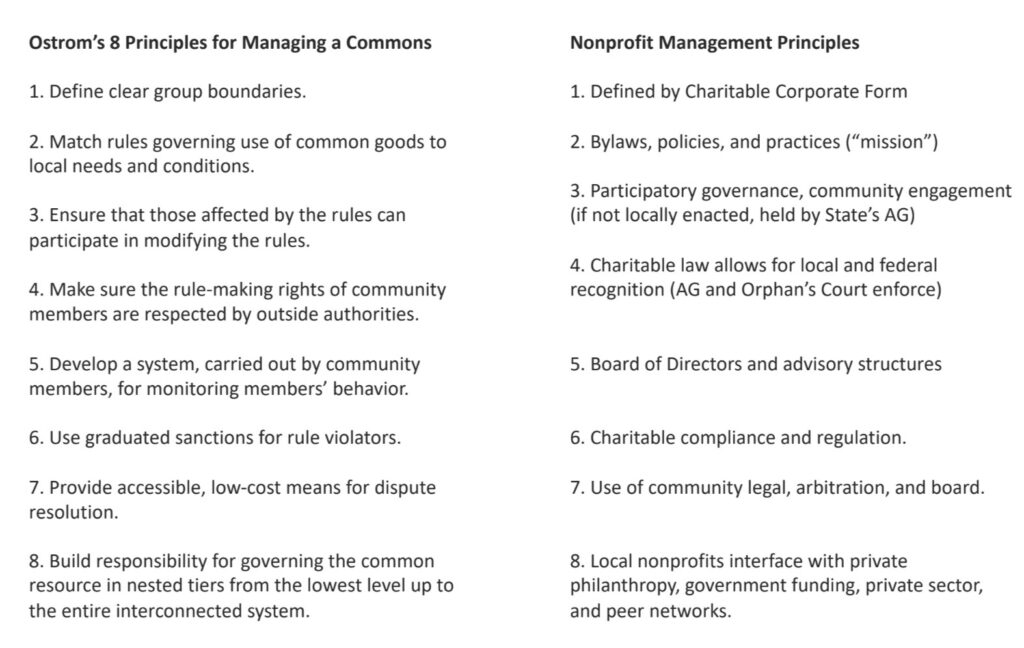

What she found was a remarkable commonality in how commons are stewarded, despite there being no direct communication and vast gulfs of geography, culture, and language between the various commons stewards. In fact, they all exhibited a set of practices and relationships that she was able to codify into Eight Principles for Stewarding a Commons. This ground-truth work and her mathematics earned her the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009–the first woman to receive this prize. Reading Ostrom’s Eight Principles for the first time I was immediately struck by the similarities they hold with basic concepts of charitable law and the stewardship of nonprofit resources. There seems to be some kind of deep-seated, shared genesis of human thought at work here between the inspiration and legacy of Elizabeth’s Act and the ancient archetypes of commons management. Maybe it’s something in the human genome, or something in the water…

We conclude this speculative historical trip, marked by leaps of logic and time, with a set of suggestions and provocations, which we will explore further in future writings.

The status and attributes of commons and nonprofit assets share many similarities, but also notable differences, largely stemming from the private-sector’s imprimatur on the laws and management of the contemporary nonprofit sector. And our historical sketch suggests a possible intellectual archaeology of the nonprofit sector in early notions of commoning. For example, most nonprofits are managed through top-down structures with governance provided by people completely outside of those served by the charity. And “business model” dominates discussions of best practice. Yet, the current social and racial justice campaign to mollify or eradicate the white-normative practices of the nonprofit sector finds itself focusing on values, practices, and ideas at the center of commoning: governance by beneficiary communities, economic solidarity, and ongoing social tie building and learning, to name a few.

Despite the suggestive nature of these observations, we are left with more questions than answers: is the modern charitable sector, and its multinational equivalents, a latter-day manifestation of Justinian’s res communes? Might then the nonprofit sector, in all its failings and shortcomings, be a perverted and disfigured commons sector? If so, is the project to return the nonprofit sector to its roots in commoning, purging it of its infection of private sector thinking? Would such a cleansing cure its ills and usher in a renaissance?

I am not yet ready to declare the problem and solution so simply dispatched. Commoning seems to be one of the threads to keep pulling on. It has something to contribute to the contours and customs of the Undersector. But there are other ideas and dynamics that lie outside the discourse of commoning that appear to promise their own revelations about the workings of the Undersector. And there is the persistent question of whether we can escape the hegemony of res privatae and its contemporary progeny, Neoliberal Capitalism, long enough to chart a course to another shore.