The Story of the Philadelphia Art Alliance in Several Acts

Act 3 – Crisis of Institution

The Philadelphia Art Alliance celebrated its centenary in 2015 with the exhibition Home is Where You Hang Your Hat. The show presented a collection of site-specific installations from a group of design practices, each responding to the history of the Alliance and its grand but clearly domestic architecture. The exhibition was critically well received and its production, in my view, did not deal the fateful blow to the organization. It did, however unwittingly, mark a symbolically rich point of inflection in the Alliance’s history: the beginning of the end of the institution, which would find itself merged with The University of the Arts just a few years later.

The subject of home at the center of the exhibition, situated in the context of a public arts institution, offers a concise glossary of the tensions between ownership and stewardship at play in the Alliance’s final years. The physical “home” of the Alliance organization was a literal house, Christine Wetherill Stevenson’s home, a place of private sanctuary and living that later became an entirely public space. Though admittedly, this public-private duality was embedded in the original design of the building itself; bourgeois domestic architecture always included both public receiving rooms and private spaces. It is not surprising that these public spaces from the original home’s design became the most fitting to support the public programming of the Alliance.

It is irresistible to note that the mansion also contained an extensive service wing, used to house and offer unseen passage to the generous staff needed to maintain a building of that size. For the public institutional life of the Art Alliance, from 1926 onward, these spaces remained largely unused, as their warren-like configuration were incommensurate with modern life-safety codes required for public access. So, the house went without its caretaker spaces, whose denizent services were never quite replaced by the public institution. Perhaps it’s fitting that the costs and labors of deferred maintenance were the final crisis accelerant for the institution–the house’s own revenge for the Alliance’s inability to staff its physical plant.

Understanding the problem- financially driven mission change

From my entry into the Philadelphia cultural community in 2000 I maintained a regular touch to the Art Alliance, either through close colleagues who ended up as staff or through my role as a volunteer panelist for the Philadelphia Cultural Fund’s annual general operating grant program. As such, I was often assigned to the Alliance as their “advocate” responsible for a site visit and digging deeper into their organizational dynamics to make their case to the full grant panel. The issues were always the same: challenges with finding the right programming niche among the city’s rapidly diversifying cultural ecology, addressing the need for racial and socioeconomic diversity in leadership, audience and programs, and board overreach into management matters.

In late 2015, the Alliance reached out to me in my role as founder and director of CultureWorks Greater Philadelphia, where at that time we had a nonprofit management consulting program, alongside work as a comprehensive fiscal sponsor. The goal of the engagement was to create an updated Strategic Business Plan capable of repositioning the Alliance’s work in a manner that would promote more earned revenue and help address a long-standing (and growing) structural deficit that was draining cash reserves and setting the organization on a course toward a fiscal cliff.

It’s almost cliche today to note how the thrall of owning real estate in the nonprofit sector often becomes the undoing of nonprofit mission. It’s very easy for a nonprofit’s mission and programs to fall financial hostage to the demands of facilities. As much as buildings can be a resource and positive asset for nonprofits, they can also become the sole driver of resource allocation, sapping energy and resources from the original mission.

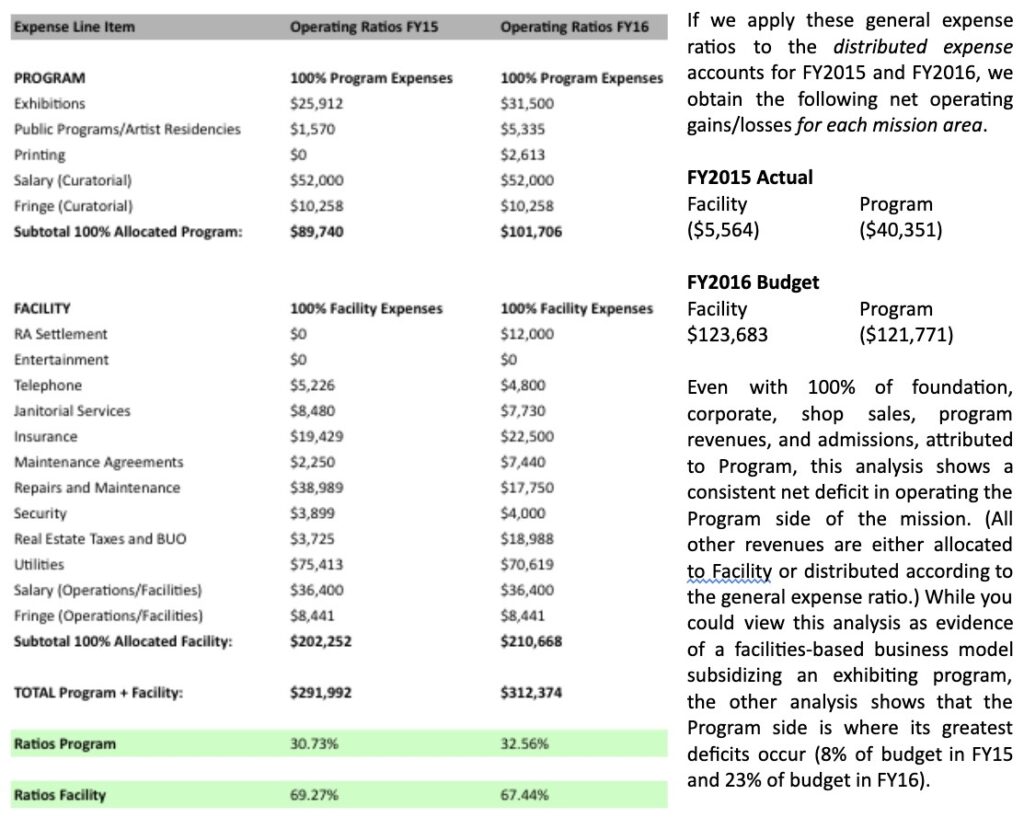

At the point I was engaged, the Alliance was no longer an arts organization. It had, in fact, become a preservation organization. There’s an old saying about firms, “If you want to know what a company values or does, look at how it spends its money.” While I’m always reluctant to financialize mission, there is some truth in that. We conducted a financial analysis that showed that the majority of the Alliance’s financial and human resources, at least in more recent years, was going toward nursing the building along with a fraction (a ratio of 2:1) being raised and spent on actual arts programming.

This news was a shock to the board. They knew that the building required a lot of care and feeding, but seeing the proportions in financial terms cast the problem in sharp relief. While maintaining Catherine Wetherill’s mansion had always been part of the mission deal, it was now fast becoming the whole deal.

After taking a good look under the organizational hood and scanning the cultural landscape, it was clear that a deeper programmatic intervention would be needed to turn the ship around. The Alliance had already identified contemporary craft as a potential niche to occupy, considering the rapid growth in attention to the “maker” community and renaissance in craft and artisanal trade production, in particular in Philadelphia. But exhibition-based programming would not be enough; competition for audiences was too great to build income on admissions alone. We hatched the idea doubling down on craft and transforming the Alliance into a hub for craft, including spaces for actual making–a contemporary craft coworking space. This transformation, which would require significant capital investment, would still need to have happened rapidly to stem the financial bleeding. I was skeptical about whether there was enough time, and more so, whether there was enough energy left in the board and leadership for another rescue attempt after several decades of managing from one crisis to the next.

Breaking through negative escalation of commitment

At this point, dwindling operating cash was driving the timeline. It was the end of the line of several decades of bailouts from the Chairwoman, as well as liquidation events aimed at shoring up finances. About a decade prior, the Alliance had sold an adjacent parking lot with the intention of banking the funds as a quasi-endowment, which was never terribly well defined by the board. The proceeds from the sale were not enough to generate meaningful interest, and so “endowment principal” was drained year over year to balance deficit spending. The organization was about six months from a position of illiquidity and the threat of having to declare bankruptcy and restructure accrued debt.

Nonprofits die when they run out of will, not when they run out of money. This is intrinsic to the idea of “permanent failure” developed by Marshall Meyer and Lynne Zucker, introduced in Act 2. The organization may be failing financially and operationally, but the personal and professional interests of the board and management keep things going at all (any) cost. I have seen many smaller (and not-so-small) nonprofits completely run out of cash with a negative balance sheet and still carry on for an extraordinary amount of time. Human will is the currency of account in a state of permanent failure, which is always signaled by a loss of financial currency.

This force of human will is often (always?) the result of “negative escalation of commitment” by people with the means (time and/or money) to commit. Negative escalation of commitment is a psycho-economic phenomenon studied in management and economic theory: in the face of escalating or repeated losses or stasis, one keeps investing out of an intensifying hope for return or progress. What seems like tenacity can become “throwing good money after bad”, the essential motivation behind gambling. Fundraising and gambling have a lot in common. They are both premised on getting an individual “invested” in putting money on the table with the murky return of winnings (if at a casino) or charitable legacy (if at a nonprofit). In both cases, the more money they put on the table, the more emotional investment accrues, and before you know it, you have a long-term donor (or a degenerate gambler).

It became clear that more drastic measures would be necessary to address the ongoing bleed, and that another bailout from the Chairwoman would not solve the underlying problem. Indeed, she was deep into a cycle of negative escalation of commitment. She had seen the institution through several such crises and was clearly tired and in search of a socially respectable and sufficiently elegant exit, one that would not sully her reputation, nor that of her late husband, whose money had been bolstering the Alliance for years.

The rest of the board was also in a position of negative escalating commitment, driven by similar social and emotional motives. They did not want to be the board that “killed the Art Alliance”. There were feelings of regret, fatigue, anxiety, and failure. The Alliance had become a perfect storm of negative escalation of commitment joined with permanent failure, a lethal mix. When this dynamic sets in at the governance or major donor level for nonprofits, sometimes the only solution is that the patient and the disease need to die together. If even the slightest corporate husk of something called the Philadelphia Art Alliance were to remain, it would have been likely that the Chairwoman (or another Rittenhouse socialite) would step in and try to raise it from the dead. It would take more than insolvency to break the Munchausen-by-Proxy cycle, and it was the whispered will of many in the cultural and funding community that euthanasia might be in order.

Even with all of this collective fatigue, the board and Chairwoman were still resistant to wind up the organization. In the fourth and final act of this series, we’ll explore how the fear of “nonprofit death” is wholly a pathology of ownership thinking, the dominant ontology of the private sector and by infection, the nonprofit sector. Ownership thinking narrows the horizon of possible futures to market-driven solutions. It constrains our thinking to only a certain set of outcomes. When applied in the nonprofit sector, where such thinking has no native place, we can find it produces a kind of economic and emotional entrapment. With market-based solutions having failed the institution, the only way out is through submitting to inevitable failure and death.

Reframing the problem through stewardship thinking, however, opens a broader horizon of possibility and allows us to exit a paradigm of death and failure into a paradigm of evolution and regeneration.

Stay tuned for our four and final Act: Resolution and Conversion.