The Story of the Philadelphia Art Alliance in Several Acts

Several years before the pandemic, I was engaged by the Philadelphia Art Alliance, an arts nonprofit, to consult to help them navigate a growing crisis of organizational sustainability. The below account, released serially over the course of the next week or so, is my account of the evolution of the Alliance–the challenges of relevance, solvency, mission reinvention, and ultimately, the process of dissolution and disposition of complex resources. It contains a constellation of lessons in how private sector ideas of ownership, inappropriately applied in the nonprofit sector, can significantly pervert or utterly subvert the process of stewardship, despite well intended actors. For this account, institutional names have been retained, as all involved are public charities and all transactions are a matter of public record. References to private individuals are made only through title or role.

Act 2 – Evolution to Descent

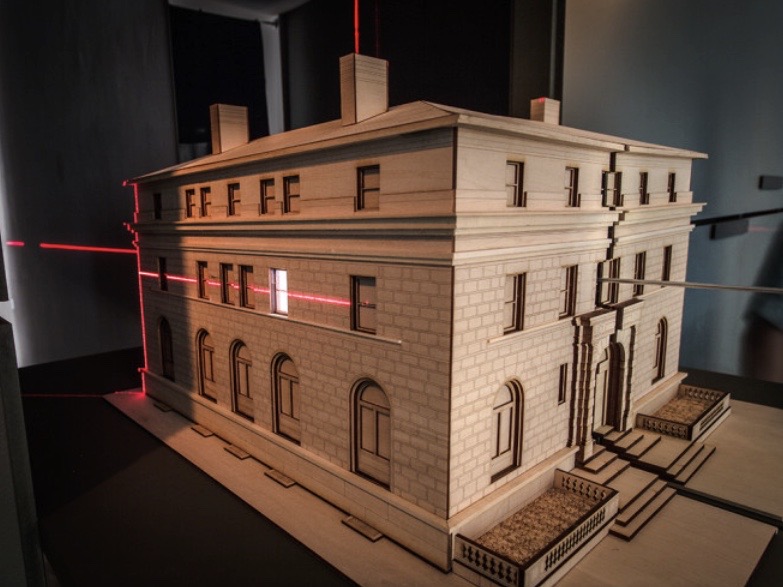

The Philadelphia Art Alliance, in its early days operated under a membership model, mixing support of and by the city’s gentry and amateur artists with the promotion of career artists, emerging and established. While the performing arts were part of the mission of the Alliance, the Wetherill mansion was never terribly wieldy to that purpose, other than presenting concerts of chamber music and other smaller ensemble programs. Dance, opera, and theatre, which all generally require more specialized and purpose-built infrastructure, remained represented among programming more in spirit than actuality.

I will not attempt a detailed history of the Alliance’s artistic programming other than to sketch it in the broadest strokes, as the challenges to reinvent and find an artistic niche within an increasingly crowded cultural landscape was one of the currents that contributed to the demise of the institution. Despite the limitations on the venue, early art exhibits included such luminaries as Mary Cassatt (whose brother, Alexander, lived nearby on 19th Street), Man Ray, Andrew Wyeth, and Antonio Gaudi. And approaching the mid-20th-century, the Alliance hosted performances and readings by Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Alvin Ailey, and E. E. Cummings. The Art Alliance established a solid reputation for being a presenter of high-quality exhibits by leading artists from Philadelphia and beyond. By the 1940s, however, competition for attention among a growing set of institutional philanthropies and arts audiences began to exert different pressures on the Alliance, its leadership and programming.

Like many of its rust-belt peers, Philadelphia saw the conversion of its industrial wealth into institutional philanthropy following World War II. This arose, in part, out of the strong social democratic ethos established by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and its signature program, the Works Progress Administration (1939-43), through which Philadelphia saw tremendous cultural investment. The William Penn Foundation (today $2.2 billion in endowment), built on the Rohm & Haas chemical and pharmaceutical fortune, was established in 1945, followed quickly by The Pew Charitable Trusts in 1948 (today $6.7 billion in endowment), consolidating multiple family trusts of the Pew family, heirs to the Sun Oil Company fortune, later Sunoco. These became the foundation of Philly’s private philanthropy, only to be matched in scale later with the giving of H.F. “Gerry” Lenfest, who liquidated Lenfest Communications in 1999 for $6.7 billion and became, along with his wife, the city’s premier cultural philanthropists from the 1990s through his death in 2018.

Adding to the cultural flourishing enabled by these private philanthropies was the advent of public arts funding, initiated by the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts in 1965 under the Johnson administration. This, in turn, led to the emergence of the first state and regional “arts councils” as government re-granting arms. The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts was established as one of the first, also in 1965. Philadelphia’s own municipal funding commitment to arts and culture emerged from the federal model and was largely enacted through discretionary spending by City Council on pet projects in their districts, a process entirely based on currying political favor. A more open and equitable model for city funding for the arts appeared in 1991 with the founding of the more politically independent Philadelphia Cultural Fund.

The growth and evolution of institutional and government funding for the arts resulted in a proliferation of cultural institutions in the latter half of the 20th century, mostly small to midsize in budget and representing a staggering breadth of specialization. Examples include Kelly Writers House, Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, Institute for Contemporary Art, Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia Ballet, Philadanco, Taller Puertorriqueño, the African American Museum of Philadelphia, Philadelphia Clef Club, and later Arden Theatre, Wilma Theatre, and a host of small producing theatres, contemporary music, and visual art organizations. Today, the Philadelphia Cultural Alliance alone represents close to 350 arts organizations and estimates the surrounding region to be home to close to 2,500 cultural nonprofits.

Against this backdrop of proliferation, the Philadelphia Art Alliance quickly lost its multidisciplinary novelty and faced growing competition in audience and philanthropic attention. This was compounded by identity and leadership challenges. At task was the organization’s evolution from an early 20th Century club for wealthy Rittenhouse Square society to a more “modern” or “professional” nonprofit organization. Part of this evolution entailed the struggle to transition from the early 20th-century model of philanthropist-as-manager to that of the nonprofit management professional. The latter emerged over the later part of the century, reaching its stride in the 1980s and creating today’s distinct class of nonprofit management professionals. (At present, there are close to 300 colleges and universities with specialized nonprofit management programs, degrees that were decidedly rare until the 1970s.)

The Alliance proved resistant to this evolution in management model, cleaving persistently to its DNA as a largely donor-managed institution. Part of this resistance may be attributed to its location on Rittenhouse Square, one of the few parts of Philadelphia that remained fairly socio-economically stable during the boom-and-bust of post-industrial America. From the founding of the Alliance in 1915 to today, the Square has remained one of the city’s most expensive addresses and home to the monied elite. The proximity to wealth and the enduringly clubby vibe of the Alliance with its lavish mansion ensured a steady progression of philanthropic interest from denizens of Rittenhouse. It was their Alliance, a club for exercising philanthropic interests and hobnobbing with peers.

For much of the 20th century, the philanthropic and management classes managed to work relatively well together to maintain the Alliance and its programming. Starting in the 1990s and accelerating in the early 2000s–when I returned to Philadelphia and started working in the cultural sector–the elite identity, expressed through its leadership and audience, began to chafe against growing demands from funders for more professionalization and diversity in both leadership and programming.

By the mid-aughts, a pattern was emerging of experienced executive directors struggling against the will and whims of monied board members, usually one board member in particular, a figure we will call the Chairwoman. The Chairwoman, a role that was occupied by several Rittenhouse figures over this period, provided generous support to the Alliance, but also exerted extraordinary control over staff and programming, reaching beyond the role of fiduciary and treating the Alliance as a platform for their own vision and ideas. In many ways, the Chairwoman may be seen as embodied the spirit of founder Christine Wetherill Stevenson, an unwitting receptacle for founder’s prerogative–a true institutional geist. While the Alliance managed to attract a succession of seasoned and very capable managers and curators, up to the end, none stayed long once they realized they were to be mere factota of the Chairwoman.

The pattern of micro-management and often fickle and unpredictable exertion of control over all aspects of the Alliance by the Chairwoman begat a revolving door for the paid staff and chronic institutional instability. This proved a hard cycle to break, as its failures were mitigated and masked by genuinely beneficent philanthropic intentions. The Chairwoman’s overreach would drive management and the institution into various localized failures, eroding confidence from the institutional funding sector and arts community, and sending the organization into a moment of financial crisis. At that moment, the Chairwoman would muster her financial resources (and those of her friends) and “rescue” the Alliance from its poise on the precipice. This pattern, a kind of institutional Munchausen-by-Proxy pathology, became so pronounced by the second decade of the 2000s that the Alliance gained an eye-rolling reputation within the funding and arts community for being hopelessly held hostage by wealthy dilettantism.

As we will continue to explore in the Undersector, the cultural construction and embrace of donor and funder control in the nonprofit sector, here embodied by the Chairwoman, are among the chief ways in which private interests intrude into and pervert the work of stewarding public trust resources. In the case of the Alliance, this resulted in a state of permanent failure, a concept coined by University of Pennsylvania faculty Marshall Meyer and Lynne Zucker in their monograph, Permanently Failing Organizations (Sage Publications, 1989). Meyer and Zucker were interested in how both for-profit and nonprofit organizations could remain chronically ineffective (or unprofitable) and remain operating, often for decades, eluding insolvency and dissolution–a phenomenon they had observed across sectors. They looked at this question of the “zombie organization” from various sociological and economic theories of the firm and concluded that there is a tendency in organizations, often precipitated by a significant change, crisis, or externality, to experience a rift in motivating interests between governance and management. Both the board and management remain interested in perpetuating the firm, but for highly divergent reasons (fear of failure, personal financial interests, reputation, etc.). This leads to an institution in perpetual tension with itself, yielding successive stresses and failures and never-quite-success. But owing to the dogged interests of governance and management, it’s never allowed to die. It exists in a state of permanent failure.

Against this backdrop of permanent failure, the challenges of jockeying for audience, both funders and visitors, continued. The Alliance turned to partnerships with local contemporary and classical music presenters, realizing it was better to outsource programming content and market pull than to compete. In its own exhibits, it focused largely on photography and contemporary craft, two areas of the arts ecosystem with comparatively lower representation among local exhibitors. To its credit, it was able to mount a number of groundbreaking contemporary art exhibits and maintain its connection to leading artists of our time. But the struggle for funding and the interests of governance mounted.

In 2015, the Alliance celebrated its centenary with an exhibit eerily entitle, Home is Where You Hang Your Hat, and including multidisciplinary works by design and architecture studios, such as Qb3, AUSTIN + MERGOLD, Moto Designshop, and PLUMBOB. While the exhibit garnered notable attention by the press and public, it was to mark a turning point toward a crisis in leadership and financial sustainability that would precipitate a final showdown between the interests of the would-be owners of the Alliance and its mission and the greater stewardship of public benefit that was owed to its community.

Stay tuned for Act 3 – Crisis of Institution & Passing of Stewardship.